Royal Observer Corps Observation Post

The Royal Observer Corps (ROC) can trace its origins back to the air defence of London during the First World War (1914-18) which was commanded by Major-General Ashmore. After the war, the continued security of the skies over Britain was considered so important by Major-General Ashmore that a network of observation posts became part of Britain’s air defences. The first two Observer Corps groups were formed in the counties of Kent and Sussex, and were followed soon after by groups in Hampshire and Essex. In 1929 the Observer Corps came under control of the Air Ministry. The Observer Corps was called out on 24 August 1939 at the start of war between Britain and Germany. From the beginning new recruits were needed.They came from all walks of life, and included women from September 1941. The main task of observers was to monitor the skies around the clock, spotting and tracking aircraft by sight or sound and reporting to control centres. Control centres then gathered the information and passed it on to Fighter Command. This important work was recognised during the Battle of Britain and the Corps received its ‘Royal’ title in April 1941. Post observers also guided friendly, but lost aircraft, to safety and some volunteered to join the Seaborne Scheme which placed observers on ships during the D-Day landings. The ROC was stood down on 12 May 1945 but was re-formed on 1 January 1947 to continue its role in monitoring the skies. However, the increased speed and height of aircraft in the new jet age made recognition of aircraft difficult for observers and in 1953 the ROC was reorganised at all levels, both to improve efficiency and to reflect changes already made at Fighter Command.

The World War II ROC Post 2/A2 was located not far behind the 1st green, adjacent to the road known locally as Sheep Plain. The exact site of the original observation post was just a few yards, perhaps no more than 30, to the north of the remaining, underground bunker. With very few trees on the Common in those days, it would have enjoyed an undisturbed view south all the way to the South Downs and Eastbourne. The bunker was finally de-commissioned in March 1968 and the resultant rubble left in a pile for the golf club to use. It was almost certainly in the way of the drive from the 18th tee and therefore an obstruction to playing golf, which led to its removal. Should it have been closer to the road and hidden within the trees which grew up after the war, it may well have survived, as so many 'pill-boxes' have done to this day as a reminder of WWII. Instead it was removed completely, no mean feat, on 25th March 1968 and the original correspondence between the Defence Lands Office and the Golf Club remains in the Club's archives, showing the termination of the £6 annual rent. The Official Plan No. 885 of Crowborough ROC Post 2/A2 is shown below. Click to enlarge, then you can enlarge even further.

A little known fact about Crowborough Common is that during the “Cold War” an Observation Bunker on Sheep Plain was manned and operated by local volunteers as members of the Royal Observer Corps. Royal Observer Corps bunkers are still quite common, there were over 1500 of them. The ROC were stood down in 1991 and most of their bunkers were simply abandoned. The Observers were not happy about what happened so when the MOD asked them to clear out their bunkers, most of them said "sod that" or words to that effect. As a result many of the bunkers that are still surviving today can be found almost as they were when they were abandoned. Brassington for example still contains three jerry cans, bunk beds, mattresses, Wellington boots, two chairs and much more. The bunker at Crowborough was seemingly abandoned in a similar sort of rush as the photographs suggest.

Many bunkers have been demolished with no photographic record remaining. Rusting of iron work in a confined space results in oxygen depletion, something that won't be apparent until the unwary pass out. There are air vents, though even if they have been left open they still will not prevent a build-up of carbon dioxide as it is heavier than air. If left shut they will be rusted solid. The main steel hatch had a very heavy counter balance weight - there were a few examples of these dropping off after linkages seized due to rusting. Age and lack of maintenance will make this more likely. Of course the prospect of flooding has to be considered as well and the vertical ladder had simple rungs of round steel bar with no grips - very easy to slip from.

The bunker on Sheep Plain, Crowborough, was opened in 1961 and finally closed by The M.O.D. in 1992. For safety reasons the site has now been made secure. For more detailed information and pictures go to the very interesting website, Subterranean Brittanica, at:-

http://www.subbrit.org.uk/rsg/roc/db/988303920.007001.htm

The Royal Observer Corps was the field force of the United Kingdom Warning and Monitoring Organisation, which was usually known as UKWMO. UKWMO was responsible for:-

- Originating warnings of the threat of air attack.

- Providing confirmation of nuclear attack.

- Provision of a meteorological service for fallout prediction.

- Originating warnings of the approach of fallout.

- Providing regional government HQs, local authority emergency centres, armed forces HQs, and nuclear reporting cells of the armed services in the UK, neighbouring countries and offshore islands with details of nuclear bursts and with a scientific appreciation of the path and intensity of fallout.

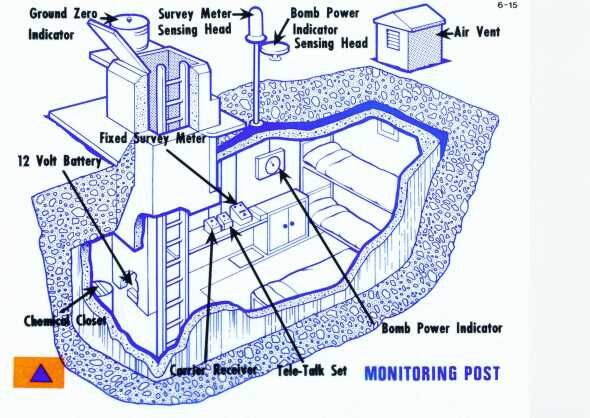

The Royal Observer Corps had given up its original role of spotting enemy aircraft by the mid-1950s and had taken on the task of monitoring the nuclear bursts and then the spread of fall out. By the late 1950s, they were equipped with some 1550 underground 3-man monitoring posts designed to withstand a blast pressure of 10 psi. The effectiveness of these posts was however questionable as most were dependent on overhead telephone lines and it was estimated in 1967 that 42% of them would lose their line in the “standard attack”. About half the posts were closed in 1968 following “care and maintenance” and the remaining 873 were closed in 1992when the Corps was unceremoniously stood down. The posts would have been able to plot the direction of a burst, its approximate size and then the passage of fall-out. The post would then report this information at regular intervals to one of 24 Group Controls spread throughout the UK. These were further organised into sectors with “blisters” for the Sector Controls attached to the Group Controls at Horsham (Metropolitan Sector), Fiskerton (Midlands), Bath (Southern), Preston (Western and national war headquarters for UKWMO) and Dundee (Caledonian). Throughout its life, the Corp’s volunteers were keen and well trained and, like the other volunteer organisations would no doubt have done their duty on the day. They were however always under strength.

One odd exception to this rule was the provision of floodgates for the London underground. During the last war, 21 floodgates had been installed to isolate parts of the tunnel network to prevent flooding if nearby rivers or sewers were breached. From 1953-1958, a second ring of 18 gates was built in case an A-bomb breached the Thames. When the Victoria line was planned it was again decided that the tubes would be used as shelters albeit unofficially and the floodgate system was expanded during 1965-1968 to cover the line north of the Thames at a time when most other civil defence projects were being delayed by lack of money. The later section of the Victoria line south of the Thames was not however given floodgate protection. Although use of the tube system and the former Deep Shelters built in London during the last war as air raid shelters was sanctioned in 1952 the idea drifted and a working party finally concluded in 1967 that it would be impractical to equip them to the required standard and their proposed use was abandoned.

NATIONAL ROYAL OBSERVER CORPS ASSOCIATION

The Heritage of the Corps

- Created and collected by ROCA.

- Donated from former serving members of the ROC

- Left to the Association in peoples wills.

- Collected by other individuals, groups or museums.

You can find an excellent article in full here:-

http://www.subbrit.org.uk/rsg/features/sfs/file_16.htm

of which, what follows below, is just a taste...

Wartime broadcasting - emergency communications - attack warning - Royal Observer Corps

British governments have recognised the importance of mass communication to both put over its own message and to boost morale since at least the time of the general Strike in 1926. During the last war, efforts were made to ensure the “due functioning” of both the national press and the BBC with this continuing throughout the Cold War. Although plans for censorship in wartime were abandoned in the late 1950s, to ensure it was giving the official message the media would have been managed at national level by a 2 tier structure originally established in the early 1960s if not before:

1. The Standing Committee on Information Policy with a Cabinet Minister as chairman. This would co-ordinate all official information and instructions to the public, maintain constant contacts with the media and generally oversee information policy. It would also direct -

2. The Media Working Party chaired by the Prime Minister’s Press Secretary, which would co-ordinate the issue of press notices and other official announcements.

The importance of broadcasting as a means of disseminating information and maintaining morale in an emergency had been recognised since the 1930s. During the Second World War the BBC had implemented detailed plans to ensure national broadcasting continued and these formed the basis of the post-war Wartime Broadcasting Service or WTBS.

The principal broadcasting centre for the WTBS during the Cold War would have been “The Stronghold”. This protected studio and office suite was built alongside the BBC’s headquarters at Broadcasting House during the war and was later absorbed into an extension of it. The Stronghold allowed the government to make nationwide broadcasts until the nuclear attack or until the seat of government left London. It also acted as the “primary injection point” for broadcasting attack warnings to the public.

During the Second World War, part of the BBC had been dispersed to a site at Wood Norton near Evesham and in the 1950s it was developed as the reserve headquarters for the WTBS. In the 1960s, a large bunker was built there to provide 4 radio studios and accommodation for 100 staff. However, its usefulness would have been limited by the difficulties in getting information to Wood Norton in the first place and then the relevance of national news to the survivors. A studio was also installed at the Corsham war headquarters in the late 1950s which was connected to Wood Norton

The initial ideas for a WTBS were sketchy but by the mid-1950s there were plans to provide a national radio service with two medium wave programmes. The BBC’s main high-powered transmitters could not be used because it was thought enemy aircraft would use them for navigation so 54 low-powered medium wave transmitters were installed around the country.

The BBC revised its plans for the H-bomb era in 1957. The object of broadcasting in war would now be “to provide instruction, information and encouragement as far as practical by means of guidance, news and diversion to relieve stress and strain”. The last phrase appears to mean entertainment, which would have been provided by pre-recorded programmes and records. The idea was to provide a national radio service possibly broadcasting 24 hours a day, although it was acknowledged that if the national electricity supply failed few people in the pre-battery radio era would have been able to hear it.

By the early 1960s, aircraft were no longer considered a major threat and the main transmitters, particularly those at Droitwich could now be used. At some time the main cable carrying the long wave (now Radio 4) service from London to Droitwich was diverted through the reserve site at Wood Norton giving it access to these transmitters. The plan from the late 1960s envisaged high powered medium wave transmitters being used at local transmitter sites which were provided with emergency generators and some fall-out protection. The decision to start the WTBS would be made at Cabinet level at a late stage in the pre-war crisis. At that point all broadcasting facilities, including BBC and ITV television would stop normal programmes and start broadcasting the frequencies for the WTBS. After an hour the WTBS would take over broadcasting one national programme originating from Wood Norton. This would carry government announcements and information interspersed with what was called “sustaining material”. Local transmitters would be used and after the attack these would allow for a regional system of broadcasts. Central government could then broadcast using this regional network. The Droitwich long wave transmitters would be held as a national reserve. Television would not be used as it was thought that it would divert people away from the vital national message to be carried by radio and would not be available after the attack.

The 1980s plans expected that the WTBS would not start until after a nuclear attack unless the broadcasting facilities nationally were severely damaged. It would provide a sound only service for only a few minutes each hour restricted mainly by the need to preserve the batteries in people’s radios. There would be no entertainment content.

Alongside the national service, it was always planned to provide a regional one. Studio facilities were planned for the 1950s joint civil–military HQs. In the long term transmitters would be installed but until that time local transmitter sites would have been used and many BBC staff would have to be dispersed from London to these sites. The RSGs had small BBC studios for regional broadcasting linked to local transmitters as did the SRHQs and RGHQs that succeeded them. So from the 1960s the main user of the WTBS would be the Regional Commissioner who would try to reassure the survivors that some form of government was still in control and to issue advice and instructions about such matters such as fall-out and emergency feeding. The local authority Controllers would be able to use the regional facilities to give out local messages. However, although broadcasting was seen as a vital service, the money was not made available for these regional facilities and as late as 1970 it was reported that it would take several years to set up a completely effective regional network.

At various times during the Cold War thought was given the continued operation of the BBC’s External Services but the plans seem to have been very confused. During the 1950s suggestions were made that 5 country houses used for the purpose during the Second World War should be refurbished but these ideas were generally not pursued and by the end of the decade the idea of a post-war external service had been abandoned. There was however a suggestion in the late 1960s that the former site of the wartime Aspidistra secret transmitters should be used for the purpose. The idea does not appear to have been implemented but it is interesting as the site would later be used in the 1980s for the new Crowborough RGHQ.

And the article continues at greater length here:-

http://www.subbrit.org.uk/rsg/features/sfs/file_16.htm

And finally, the BBC One Show - 'Down the Hatch'

On Wednesday 13 February 2013, the BBC broadcast an episode of their popular nightly programme ‘The One Show’ with Matt Baker and Alex Jones. What was unusual about this episode was that it contained a 5 minute article on the nuclear role of the Royal Observer Corps. The filming took place last October in the south east of England and featured Lawrence Holmes of 10 Group and Bryan McCarthy of 1 Group. The article was filmed by Icon Films of Bristol with 6 hours of filming being edited down to just 5 minutes air time. The locations used were the restored ROC Post at Cuckfield, Sussex, an ‘explosives’ site near Brighton, Maidstone ROC Control and the preserved Regional Seat of Government at Kelvedon Hatch, Essex. Two unusual and unique experiments were carried out. The first was to recreate the ‘spot’ made on the GZI printing out paper using a high powered flood light and the second was to replicate the firing of the ROC Fallout Warning maroon to record on film the explosions forming the morse letter ‘D’. It is thought that this is the first time for many years that the ROC has received this level of media publicity on a major TV channel and on a very popular show which was broadcast all over the UK.